Is there anything more Floridian than a flamingo? They’re everywhere. Pink plastic ornaments dotting lawns. On cocktail swizzlers and motel signs. But what about real Florida Flamingos?

Real, live Flamingos occasionally show up in the Everglades. A couple years ago a big flock showed up in a Palm Beach County stormwater treatment area. But the official story is that these birds don’t belong here. That Florida’s flamingos were all hunted out of existence back in the 19th century.

Now, in a paper published on Wednesday, Feb. 21, in the American Ornithological Society journal The Condor, a team of South Florida researchers is making the case that the conventional scientific wisdom of almost a century is wrong. Florida in fact has flamingos – real birds, not the plastic kind.

It’s a South Florida detective story – the case of the NOT missing flamingos.

Capturing Conchy

It started with Conchy. In 2015, three flamingos showed up at the Navy airfield on Boca Chica Key, about five miles from Key West. Big birds like herons and egrets sometimes show up on the airfield, and the Navy scares them away.

Otherwise, the bird could get sucked into the engine and crash a $70 million jet. (That would be bad news for the bird, too.)

One of those three flamingos — a bird that eventually acquired the name Conchy — was a problem.

“Conchy would not leave,” said Steven Whitfield, a conservation biologist with Zoo Miami. “They couldn’t harass him away.”

The team at Zoo Miami had been looking for a flamingo- they wanted to release one with a satellite tracker. A flock of 147 flamingos showed up in Palm Beach County stormwater treatment area in 2014 and raised questions. Where were these birds coming from?

Conchy was captured and fitted with a satellite tracker. But there was yet another problem.

“The state told us that we couldn’t release non-native species,” Whitfield said. “So that’s when we started digging into the question of, are they really non-native?”

The state’s official position is that flamingos may occasionally wander through from Mexico, Cuba or the Bahamas — but the flamingos in Florida are more likely escapees from captive populations.

Whitfield pulled together a team of people who research Florida’s wading birds to ask the question: Does Florida have flamingos?

The team included researchers from Audubon of Florida’s Everglades Science Center in Tavernier, in the Upper Keys. That’s been the base for studying and documenting wading birds in Florida Bay and the mainland Everglades since the 1930s, before the establishment of Everglades National Park.

The Hialeah racetrack doctrine

Jerry Lorenz is the director of research for Audubon Florida and he heads the Everglades center.

“When Steven brought us all together, the first words out of my mouth were, ‘You know those are just escapees. Why are we even talking about this?’” Lorenz said.

Lorenz has been studying big pink birds on Florida Bay for almost 30 years. But he studies roseate spoonbills, not flamingos.

He does see flamingos on the bay occasionally. He saw a flock of 25 flamingos on his first research trip to Sandy Key, in the western part of the bay, in 1989.

“I was shocked,” Lorenz said. So he asked his boss if the flamingos were here all the time.

His boss told him they were pretty rare, and 25 was a big group to see.

Lorenz asked where they came from. The answer: “All the historical evidence indicates that they were escapees from Hialeah racetrack.”

“Historical evidence” in this case means the opinion of the researchers who had been studying wading birds in Florida Bay since the 1930s.

Especially the man who established what is now called the Everglades Science Center in Tavernier – Robert Porter Allen.

Allen is best remembered for his work to study and protect the whooping crane – those birds were down to 15 individuals in the 1950s. In Florida, he focused largely on roseate spoonbills.

And he was the authority on the American flamingo, traveling to the Caribbean and the Bahamas. He was the National Audubon society’s director of research. He literally wrote the book on flamingos, a 258-page study published by the National Audubon Society in 1956.

Sandy Sprunt, who followed Allen as director of the science center, studied flamingos in the Bahamas for his master’s degree. He was still the director when Lorenz got there in 1989.

“So these two guys really knew their flamingos and both of them were insistent that these were escapees,” Lorenz said.

Allen arrived in the Keys in the late 1930s. That was the same exact time that the flock of flamingos imported from Cuba by the owner of the Hialeah racetrack started to nest and reproduce.

“That gave him the impetus to say, ‘Yeah, those are escapees.’ Without any documentation,” Lorenz said. “And I think that just stuck with him when they kept showing up in ones and twos only.”

Flamingos that Allen and others occasionally saw could have been escapees from the racetrack. But “there is zero evidence for that,” Lorenz said. “And now that we are seeing flamingos come in here in singlets and pairs from elsewhere, why wouldn’t they have done it then, too?”

The correlation of captive flamingos in Hialeah became the causation of the captive escapee theory. And over the decades it was never seriously questioned.

The search for flamingos: Back in time

The search for flamingos: Back in time

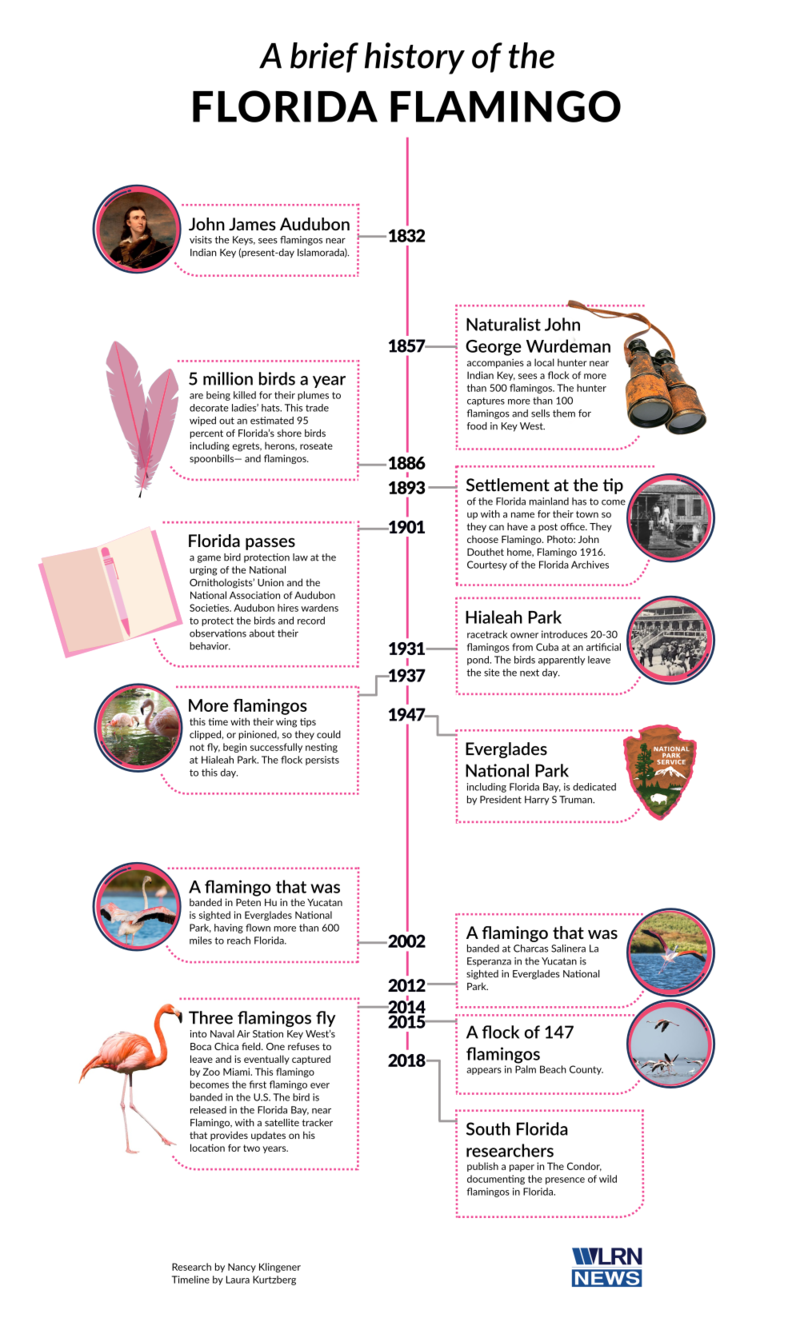

The research team started its search for flamingos by going back in time. Whitfield said that was to look for evidence of flamingos in Florida before the plume-hunting trade took off in the late 19th century.

“Some of the sources that we had were written by scientists in the late 1800s who were specifically down in South Florida to study birds,” Whitfield said. “Other sources were things like the journals of an officer in the Seminole Wars, who just happened to describe hunting flamingos in the 1820s or ‘30s.”

John James Audubon himself saw flamingos in 1832 near Indian Key, an island off Islamorada, in the Upper Keys.

He later wrote that seeing the birds was the height of his expectations: “Far away to seaward we spied a flock of Flamingoes advancing in ‘Indian line,’ with well-spread wings, outstretched necks, and long legs directed backward. Ah! reader, could you but know the emotions that then agitated my breast! I thought I had now reached the height of all my expectations, for my voyage to the Floridas was undertaken in a great measure for the purpose of studying these lovely birds in their own beautiful islands.

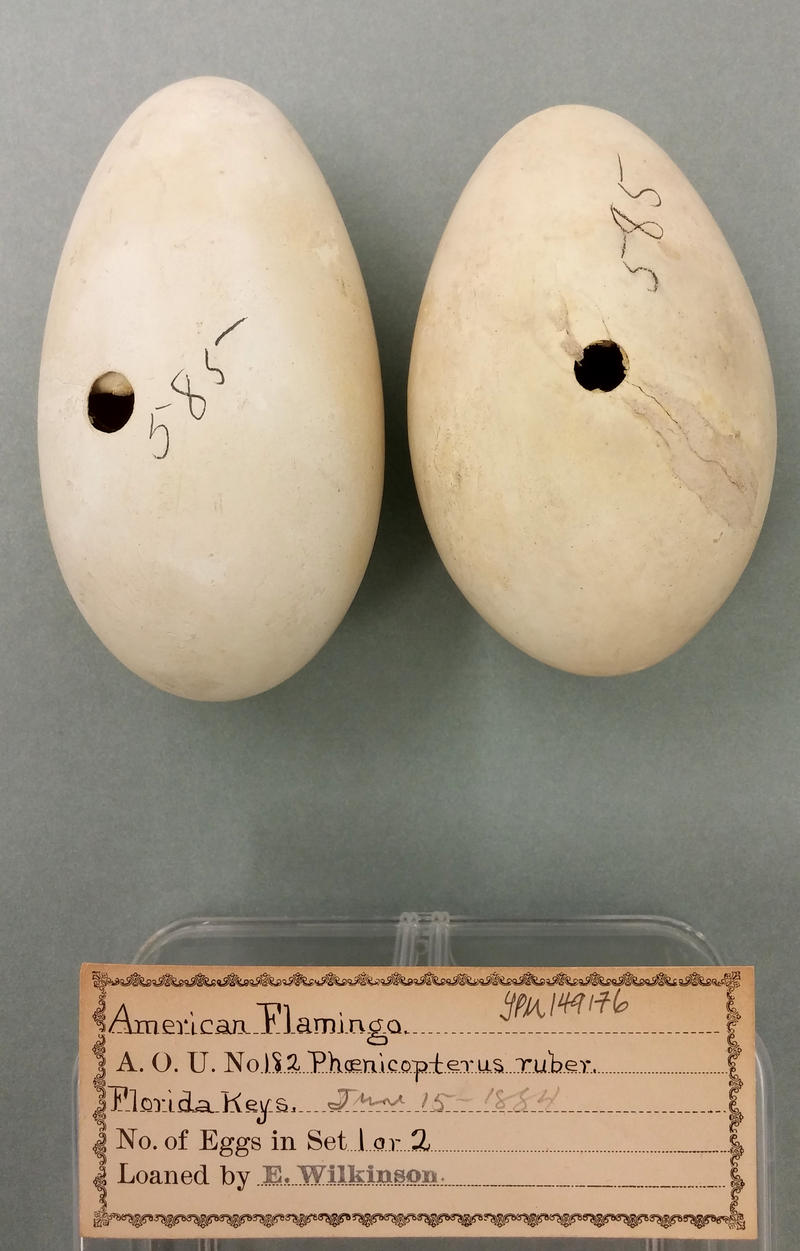

The researchers used 21st-century databases and digitizing projects to look for 19th-century museum specimens. Not only of adult flamingos but also flamingo eggs, to find out if the birds once nested in Florida.

“In the late 1800s, collecting wild bird eggs was a weird but somewhat popular hobby,” Whitfield said. “I think it was kind of like Pokemon Go, but real.”

He found four specimens in museum collections that were labeled as flamingo eggs that had been collected in Florida.

So it was pretty clear flamingos were in Florida in big numbers in the 19th century. They were hunted for food and later in the 19th century for the plume trade.

Florida passed a law protecting the birds in 1902. The researchers looked for accounts from the Audubon wardens who monitored birds in Florida Bay and the Everglades before the national park was established in the 1940s. Those records were kept at Audubon’s Everglades Science Center in Tavernier.

“The wardens were required to write up a weekly report of their bird sightings and it turned out to be a fascinating and very important and useful historical dataset of bird numbers,” said Peter Frezza, Audubon of Florida’s research manager for the Everglades region at Everglades Science Center.

And they had lots of data from a quiet cadre who had been documenting and sharing information all along.

“What’s great about birds is that people like to watch them,” Whitfield said. “And since birding is kind of a sport, rare bird observations have been reported by birders for decades now.”

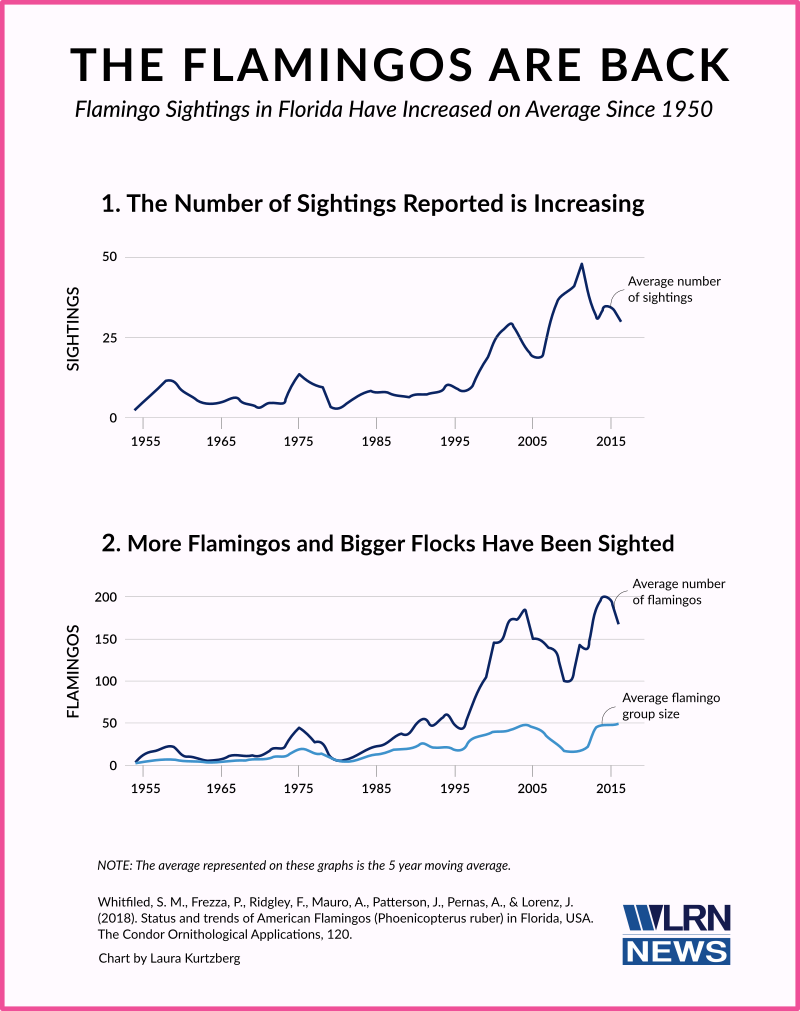

The number of reports, and the numbers of birds reported in each sighting, steadily increased through the years. And really took off in this century.

‘Those are not spoonbills’

Frezza was out with a colleague doing some research in Mud Lake, an interior mangrove area in the Everglades in July of 2004.

The boat was running at idle speed through the shallow water.

“And just on the horizon was this huge line of pink. And we were like, ‘Oh my gosh. Those are not spoonbills. They’re too big. Those are flamingos.’”

It was a flock of 64 flamingos. Frezza also works as a fishing guide and he had already been collecting observations and photographs of flamingos from his fellow guides as well as researchers on the bay. That information is part of the new study.

Like everyone who worked at Audubon’s Everglades Science Center in Tavernier, Frezza was told the Florida flamingos were racetrack escapees.

“And I believed that until I started personally observing them and their behavior and then also observed the birds at Hialeah and started forming my own opinion that — no way. These were wild birds. They were in wild places, acting very wild,” Frezza said.

The next question: If there are wild flamingos showing up in Florida, where are they coming from?

Researchers hoped Conchy, the flamingo captured at the Navy base near Key West, would help answer that question.

The Zoo Miami team got permission to release Conchy after pointing to flamingos spotted in the Everglades in 2002 and 2012 with leg bands they got as chicks in Mexico. That proved those birds were definitely not escapees. They released Conchy with a satellite transmitter attached to his leg.

“And what we expected was that Conchy was going to fly to the Bahamas, fly to Cuba, fly to the Yucatan in Mexico,” Whitfield said. “He was going to tell us, finally, where the flamingos in Florida come from. In that, he was a failure.”

Conchy, it turned out, was a homebody and the satellite tracker showed that he stayed in Florida Bay. He was occasionally spotted with other flamingos.

Frezza says Conchy has still contributed to knowledge about flamingos

“He proved that flamingos can live year round in Florida Bay,” Frezza said. “Florida Bay can sustain flamingos. On an annual basis. Which is pretty cool.”

Conchy’s satellite transmitter stopped working shortly after Hurricane Irma but he has been spotted a couple times since the storm. He stands out from other flamingos.

“He’s got a large blue leg band that says U.S. 01 because he’s the first and only flamingo ever banded in the U.S.,” Whitfield said.

Now it will be up to the state and federal wildlife agencies to decide whether they should treat flamingos as local birds, that deserve protection, instead of officially considering them exotics or escapees.

“They’re supposed to be here,” Lorenz said. “They’re not escapees. You don’t treat them like an exotic species. We have to treat them like a native species.”

Pink birds, coming and going

South Florida was always at the northern edge of the range of the American flamingo. But with climate change, that range could be expanding.

That’s what appears to be happening with roseate spoonbills, said Lorenz, who has been documenting their numbers dwindling in the bay, even as they increase on the mainland.

“If you go back to the 1800s and look at what was documented at that point, roseates never nested north of Tampa Bay on the Gulf coast of Florida and north of Merritt Island on the east coast,” he said. “Now they’re nesting in South Carolina … So these birds are changing their ranges as the temperatures get more and more suitable to their habitat.”

Another clear example of changing ranges: Audubon researchers this year are documenting the first-ever recorded pair of neotropical cormorants to nest in Florida Bay.

“I expect to see more and more of this,” Lorenz said. “So what do we do with those birds? As the climate gets warmer here, we’re going to get more and more tropical species. Do we treat them as introductions, or not?”

Some of the historical accounts mention up to 2,500 flamingos in Florida Bay. Lorenz said he would love to see that kind of massive flock return.

“That’s an unbelievable sight. I’ve seen that in Cuba. I’ve seen that in Mexico,” he said. “It just is stunning.”

In the meantime, he and other researchers can keep spreading the news that they have solved the case of Florida’s missing flamingos. The flamingos have been here all along. Hiding in plain, pink sight.

Source: The Case Of The (Not) Missing Flamingos: A South Florida Detective Story | WLRN