As with most crocodilians, the Florida Keys American Crocodile courtship and mating are stimulated by increasing ambient water and air temperatures. Reproductive behaviors peak when body temperatures reach levels necessary to sustain hormonal activity and gametogenesis.

In South Florida, temperatures sufficient to allow initiation of American Crocodile courtship behavior are reached by late February through March. You may begin seeing more activity by female American Crocodiles searching for and digging nesting sites along the Florida Keys.

Like all other crocodilians, the mating system of the American crocodile is polygynous; each breeding male may mate with a number of females (Magnusson et al. 1989). Males typically establish and defend a breeding territory from late February through March (Moore 1953a, Garrick and Lang 1977). Vocalizations, body posturing, and outright aggression are used to maintain and defend territories and to secure mating privileges with females that roam freely between territories. Male and female American crocodiles go through a ritualistic mating sequence prior to copulation. Courtship in this species is considered to be one of the most structured of all crocodilians, with copulation predictably following precopulatory behaviors (Lang 1989, Thorbjarnarson 1991).

You can view some videos of courtship activity from a couple of years ago here American Crocodile Videos.

Following courtship and mating, females search for and eventually select a nest site in which they deposit an average of about 38 elongated oval eggs. Reported clutch size ranges from 8 to 56 eggs (Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989; P. Moler, GFC, personal communication 1998).

Nest sites are typically selected where a sandy substrate exists above the normal high water level. Nesting sites include areas of well drained sands, marl, peat, and rocky spoil and may include areas such as sand/shell beaches, stream banks, and canal spoil banks that are adjacent to relatively deep water (Ogden 1978a, Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989). In some instances, where sand or river banks are not available for nesting sites, a hole will be dug in a pile of vegetation, mulch or marl the female has gathered. The use of mounds or holes for nesting is independent of the substrate type and may vary among years by the same female (Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989).

The success of American crocodile nesting in South Florida is dependent primarily on the maintenance of suitable egg cavity moisture throughout incubation. Predation and flooding also affect nest success. On Key Largo and other islands, failure of crocodile nests is typically attributed to desiccation due to low rainfall (Moler 1991a). On Key Largo, about 52 percent of nests were successful in hatching at least one young (Moler 1991a). Nest failures on the mainland may be associated with flooding, desiccation, or predation (Mazzotti et al. 1988, Mazzotti 1989). On the mainland, about 13 percent of nests monitored were affected by flooding or desiccation, whereas 13 percent of nests were partially or entirely depredated (Mazzotti et al. 1988, Mazzotti 1989). More recently, Mazzotti (1994) found that predation rates on the mainland increased to 27 percent, and only 9 percent of nests failed because of infertility or embryonic mortality. Most examined eggs have been fertile (90 percent, range 84 to 100 percent) (Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989, Mazzotti 1989).

Incubation of the clutch takes about 86 days (Lang 1975), during which time the female periodically visits the nest (Moore 1953a, Neill 1971, Ogden 1978a). Some females may also attend and defend their nest during incubation (Alvarez del Toro 1974, Ross and Magnusson 1989), but this behavior is highly variable among individuals and nest defense has not been observed in the U.S or Cuba (P. Moler, GFC, personal communication 1998). In Florida, American crocodiles are not known to regularly defend their nest against humans (Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989). However, all females must return to the nest to excavate hatchlings since the young are unable to liberate themselves from the nest cavity (Moore 1953b, Neill 1971, Ogden and Singletary 1973, FWS 1984). Parental care after hatching has not been reported for this species in Florida, even though this behavior has been documented in other American crocodile populations (Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989).

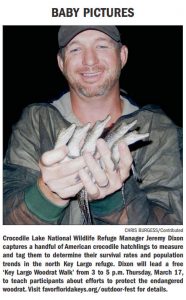

The young may remain together loosely for several days to several weeks following hatching, but they are rarely seen with adults (Lang 1975, Moler 1991b, Mazzotti 1983, Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989). Hatchling survival appears to be low in Everglades NP (< 5 percent) (Mazzotti 1983, Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989), higher at Turkey Point (8.5 percent) (L. Brandt and F. Mazzotti, University of Florida, personal communication 1998), and even higher in the more sheltered habitats of North Key Largo (20.4 percent) ( Moler 1991b). Higher survival on Key Largo has been attributed to the close proximity of nest sites to suitable nursery habitat. On the mainland, nest sites on exposed beaches are often far from nursery habitat, requiring recently hatched young to disperse Page 4-510 AMERICAN CROCODILE Multi-Species Recovery Plan for South Florida long distances in unsheltered water. Hatchlings seek shelter during the day in beach wrack or among mangrove roots when available (Mazzotti 1983). Predation during these dispersals is probably high, although little information is available to support this conclusion (Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989).

The young may remain together loosely for several days to several weeks following hatching, but they are rarely seen with adults (Lang 1975, Moler 1991b, Mazzotti 1983, Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989). Hatchling survival appears to be low in Everglades NP (< 5 percent) (Mazzotti 1983, Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989), higher at Turkey Point (8.5 percent) (L. Brandt and F. Mazzotti, University of Florida, personal communication 1998), and even higher in the more sheltered habitats of North Key Largo (20.4 percent) ( Moler 1991b). Higher survival on Key Largo has been attributed to the close proximity of nest sites to suitable nursery habitat. On the mainland, nest sites on exposed beaches are often far from nursery habitat, requiring recently hatched young to disperse Page 4-510 AMERICAN CROCODILE Multi-Species Recovery Plan for South Florida long distances in unsheltered water. Hatchlings seek shelter during the day in beach wrack or among mangrove roots when available (Mazzotti 1983). Predation during these dispersals is probably high, although little information is available to support this conclusion (Kushlan and Mazzotti 1989).

Read more about the American Crocodile here: https://www.fws.gov/southeast/vbpdfs/species/reptiles/amcr.pdf

If you suspect American Crocodile nesting on your property you can call the FWC at 866-FWC-GATOR (866-392-4286)